PROTOZINE: ONCE UPON A TIME INCONCEIVABLE

PROTOZINE: Once Upon a Time Inconceivable

View online & download PDF

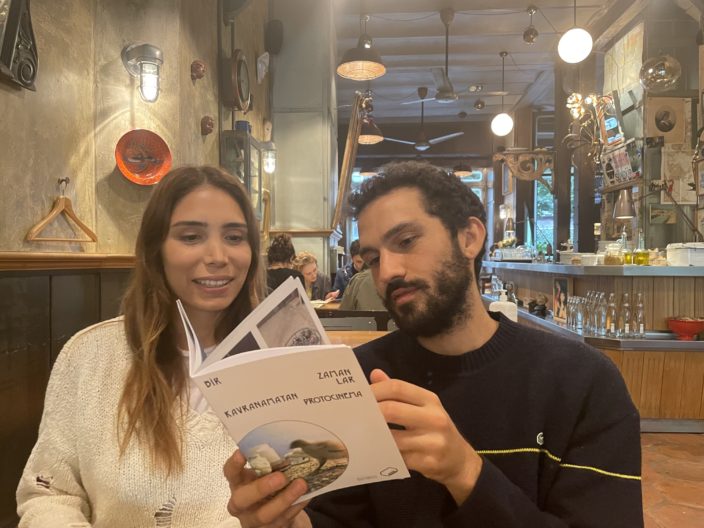

This edition of Protozine is comprised of texts by Lara Fresko Madra, Alper Turan and Mari Spirito, each elucidating the pair of conception and realization within the frame of artists’ works in the exhibition. Accompanying Once Upon A Time Inconceivable, exhibition celebrating Protocinema's ten year milestone, the texts in Protozine checks Protocinema history, its missions and actions in relation to the exhibition.

Once Upon a Time Inconceivable

by Alper Turan

Protocinema is happy to present Once Upon a Time Inconceivable, a group exhibition on the occasion of our ten year milestone, cross-examining the pair of perception and realization, and their impairments in relation to time and space, bringing together works by Abbas Akhavan, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan, Banu Cennetoğlu, Ceal Floyer, Gülşah Mursaloğlu, Zeyno Pekünlü, Paul Pfeiffer, Amie Siegel, and Mario Garcia Torres. Coming at a crucial moment of crisis and loss that urges us to rethink all establishments and reevaluate personal, local and global relationships, Once Upon a Time Inconceivable invites us to reassess curious workings of perception and realization. Through the artworks bending perceived temporalities and conceived spatialities, this exhibition sheds light on the process of discernment.

Active, relational, and hence vulnerable to manipulation and predisposed to working-outs; perception is ‘not something that happens to us or in us, but something that we do (...) We enact our perceptual experience.’’ [1] From phenomenology to neuropsychology, how we grasp and relate to the world around us has been a long lasting subject across many schools of thoughts, albeit how we process, digest and take in and hold, so to say how we conceive what we perceive has been under-speculated. From the moment of bodily encounter with an object to its so-called mental representation and to internalization which render the experience of perception mundane and turns the subject blind to the object's further capacity, this journey of perception and realization is inherently linked to art’s ontology as well. With the works of conceptual artists, the exhibition traces down the protocols of perception and problematizes the petrification of received ideas. What art can teach us about how we perceive things? How do we conceive them? How can we re-perceive and de-conceive them?

Milestone marking Protocinema tenth year (10 human year, 1 and half dog year, 0.043 Plutonian year, and so and so forth), Once Upon A Time Inconceivable also engages with the question of time and positions temporality at the heart of its inquiry. Without essentializing the time as an agent dictating new perspectives on order and ‘nature’ of things, with the works of time-based media, as well as the ones which are activated, transhaped or reconfigured with and through time, the exhibition comes to grips with the force of elapsed time and probes our perception of multiple temporalities.

Contrasting to the immensity of the exhibition space with its minimal, almost invisible presence, Ceal Floyer’s work Viewer (2011-21), a peephole installed at the glass door of Beykoz Kundura, points how we look at things, what we look at and the limits of our angles of view and visibility. In conventional household usage, peephole separates private, so-called safe space from the outer worlds that are fraught with exposures; with its one-directional viewpoint, it gives privileged positions to the insiders. In Floyer’s positioning, conversely, the distinction between inside and outside becomes vague and equalised, now the perceiver and the perceived are both exposed to one and another. Being a sculpture which is both what we look at and something we look through with, Viewer ironically plays with unfixed positions of art-viewer and art-object. Floyer’s second work in the exhibition proposes another mode of viewing. Overgrowth (2004) is a slide projection of a tiny bonsai tree scaled up to the size of a large wall. The tree’s dimensions are determined solely by the distance that the projector is from the wall which makes the distance between the wall and projector, rather than the projected image, the subject of the work. The only still image in the exhibition, Overgrowth offers a paused moment of reflection on distance and proximity, and their dispositions’ relativity.

Protocinema has a long-lasting flirtation with moving image and screen works; it takes its title from a Werner Herzog quote from his film Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) in which he comments on one of the oldest cave drawings discovered showing animals with eight legs instead of four and he speculates: ‘‘Maybe this is man’s first attempt to represent motion, maybe this is protocinema.’’ Protocinema is an ambulatory institution which is always in motion and in the pursuit of understanding and responding to the world in motion. Correspondingly, the exhibition marking its milestone both incorporates many video works and responds to its venue Beykoz Kundura, once upon a time a leather and shoe factory which now serves as a set where movies and TV series are shot.

Mario García Torres’ Spoiler Series (n.d.) featuring canvases and posters disclosing the endings of well known movies come out of a research, which asserts that knowing the end of a narrative movie actually enhances the experience of the film, suggesting how, when not focused on an unknown outcome, we maintain our capacity to read multiple layers of complexities. While his small scale canvases are scattered around the exhibition space and waiting to be discovered by the audience, the poster versions mimicking promotional movie posters are installed at various movie kiosks elsewhere in Istanbul as well as Kars, Ankara and İzmir. This gesture poses manifold questions of the artwork’s status as an authentic object versus mass-produced and received message as well as the artist's role (!) as a spoiler and experience-shifter. Most remarkably, the series put forward how one cannot damage nor spoil one’s individual experience of art, be it a narrative movie or a painting.

Without a Camera (2021) by Zeyno Pekünlü sources 325 different videos from an online video-sharing platform shot by people, machines and things, offering a remake of the film classic Man with a Movie Camera (1929) by Dziga Vertov. Pekünlü’s video runs parallel to the original editing of Elizaveta Svilova, but it replaces the camera and the cameraman with camera operator and new recording technologies such as mobile phone cameras, selfie sticks, GoPro’s and built-in computer cameras. These technologies render humans now as appendages of the devices and questions how our perceptions and realizations have been altered via new apparatus. Just like Man with a Movie Camera, Pekünlü does not follow a scenario nor a spoil-able narrative but proposes a collection of moments showing multitudes of contemporary coexistence of living and nonliving objects.

Paul Pfeiffer’s Orpheus Descending (2001), a multi-channel video of 1800 hour, displays the 75-day-life-cycle of a flock of chickens as they are being incubated; they hatch from their eggs and develop from day-old chicks to full-grown adults. While the original live version of the video, installed in the World Trade Center three months before its destruction, displayed the chickens in real time, this new version, shown in Istanbul 20 years after its first realization, brings all that has been lost along the way in changing times and spaces. Borrowing its title from Tennessee Williams’ 1947 play and loosely referring to mythological ill-fated journey to Underworld, and initially installed at the now-gone World Trade Center’s bowels where 19 escalators used to carry almost a million people everyday, Orpheus Descending was initially conceived for a passer-by audience and to propose a point of conjunction between organic and urban lives, and their different paces and temporalities. While this artwork is about different constructions of time, it is also about consciousness of the passing of time, which is synonymous with death. We witness the lives of the animals for seventy-five days, and the video ends on the last days they were together, before being sent for slaughtering. Today, after September 11 that altered the course of our lives internationally, we are being invited to witness and celebrate the lives of the now-gones.

Amie Siegel’s video, Quarry (2015), on the other hand, traces the source of marble from the largest underground quarry in the world in Vermont to its high-end destination in Manhattan real estate showrooms. The film unearths elaborate layers and strategies of recreation and simulation and proposes an alienation journey of the metamorphic rock that was once raw to become a signifier of luxury and exclusivity. We follow the marble from a cold quarry evocating a raw graveyard to shiny but lifeless sales galleries of high-end developers; marble that is associated with classical renaissance sculpture is being deployed in Manhattan condos to equate real-estates to works of art. Via long parallel tracking shots using seemingly objective gaze, Siegel’s meticulous and poetic rendering of extraction of natural resources exposes a complex economy of production and speculation without zooming in on the labor but the crucial conjunction of the concepts of labor, value and art.

Hera Büyüktaşcıyan’s new sculpture contends a different manoeuvre of unearthing and recalls the marble in a disparate aesthetic. Skindeep (2021) resonates with the site of Beykoz Kundura, once a factory that mass produced paper and leather and is currently a film set. Taking the building’s ongoing relation to skin and façade (or façade as a skin and vice versa) which as being surfaces covering but also recollecting things and in any case directs our perception, Büyüktaşçıyan invests in the morphology of surfaces that bears traces of time through material poetics. Connecting her question on skin to her ongoing research around and inspiration by the Byzantine heritage and the contemporary local politics around it which are once again manifesting through converted buildings, covered mosaics and hidden histories, Büyüktaşçıyan takes carpet as object of inquiry to activate the space. As the authorities strategically deployed carpets in recently re-purposed Hagia Sophia to cover the Christian imageries and emblematic marble grounds with thousands of square meters of carpeting, Skindeep uses the carpets to recall the memories of the marbles. The relative of skin, shield and cover, the carpets are put into a motion with the help of a structure to eventually create a melting movie stage, the decor of covering and hiding which is unavoidably haunted by what is covered and/or hidden.

The aesthetic of melting is more an active processual element in Gülşah Mursaloğlu’s new work , where she stages an investigation on heat, the actors of the underworld and their elastic temporalities, by connecting things with different temporalities to create an exhibition-long event. A part of her ongoing interest in the will of the materials and time’s contingent persistence on matters, Merging Fields, Splitting Ends (2021), Mursaloğlu creates a dynamic system that expands throughout the exhibition, employing time and heat as central agents. She uproots potatoes, and suspends them in the air after transforming them into bioplastic sheets and sewing them together, and then let us watch another transformation with the help of water that heats up in irregular intervals, generating heat and steam that are slowly disintegrating the sheets. From the heat the potato needs to grow to producing the ephemeral bioplastic sheets out of famously long-lasting potatoes, to the hot plates activated by electricity and boiling of water and its ultimate force on sheets; all the visible and invisible entropic workings of heat are components and conditions of this sculptural-installation. Heat, ‘‘the microscopic agitation of molecules’’ [2], reveals the flows between material states and how things get connected in space, communicating with one another in imperceptible ways.

Contrasting Mursaloğlu’s investigation on heat as an agent of movement, Abbas Akhavan’s work is a monument of a halt - his new sculpture uses temperature to stop movement, freezing what was once fluid. Constructed of the innards of pre-existing public fountains and of new extensions that expands the orbit of fountains, the object is frozen viscera of a speculative urban spring. From the middle ages to today, to make a spectacle of prosperity, to celebrate the running water or to provide drinking water, fountains have been at the center of public spaces in disparate times and geographies, marking meeting points. Here, what we see are idled pipes that are constantly being frosted by a cooling engine, standing like a displaced chandelier, or a misguided satellite, time standing-still. Running water is now gone and missing; splashes are ghosts. This displaced and disabled fountain is another excavation model that the exhibition brings together alongside the works of Amie Siegel, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan and Gülşah Mursaloğlu: Abbas Akhanan unearths a submerged inner system of a public spectacle. In its territorial subtlety, spring (2021) criticizes the suspended publicity, numbed actions, frosted flow whilst this fountain on pause still contains a potential splash.

What comes after perception and realization? Action? Banu Cennetoğlu’s installation ‘‘IKNOWVERYWELLBUTNEVERTHELESS’’ (2015-ongoing) embodying the title in Turkish with 24 black letter-shaped mylar balloons interrogates if knowing what we know necessarily leads to an action. Quoting from the French psychoanalyst Octave Mannoni who studied the relationship between psychology and colonialism with an indisputable bias and reductionism, this text refers to a belief in something that is at odds with one’s own experience, in a word: denial. Drawing from Freud’s theorization of fetish as at one and the same time to believe in phantasy and to recognize that it is nothing but a phantasy which no way reduces its power on individual, Manoni asserts social systems operates through forms of beliefs akin to fetishist’s disawoval so much so that the misinformation turns into belief which snowball as faith and commitment [3]. Cennetoğlu, as an artist whose practice uses and problematizes the dissemination of information, its legitimacy and illegitimacy and its distortion within the prisms of ideologies, interrogates here the information’s potential and impotency in triggering political action.

Helium-filled balloon letters are floating in the space, rearranging themselves and possibly creating new meanings, being activated and deactivated with the room temperature and architectural conditions of the space. As we know via physical laws that in the course of the exhibition, helium will escape, the balloons will deflate and the expression will deform; nevertheless, maybe they will stay intact, maybe we do not know very well.

‘‘I know very well, but nevertheless...’’ bears the logic also applicable to art’s mode of operation, it is the work of the magician whose tricks are not magic but perfect illusion. Art (art-making, art-mediating, art-viewing, or art-valuing), is about perceiving illusionary gestures, being pre-determined to investigate between the lines, constant attempt to grasp something beyond what’s already given, understanding that literal has the transcendental capacity. We act out to perceive what can easily go unperceived if we do not act it out. Artworks beg the viewers to find a meaning from the artist ‘‘while at the same time rendering it untenable’’ [4] Viewers are forced into a turning point, “the moment when they have seen everything they can, and they sense it's time to look away.” [5] Turning point is when they do not look away, they pursue the journey in and out, moving with the artwork and eventually when they get back to themselves, to their body, becoming the center of the artwork. Once Upon A Time Inconceivable is about turning points; it is an invitation for not looking away.

[1] Noë, Alva. Action in perception. Cambridge, MA: MIT press, 2004, pp. 1-5.

[2] Rovelli, Carlo. The order of time. Riverhead books, 2019, p. 21.

[3] Mannoni, Octave. "I know very well, but all the same…." Perversion and the Social Relation: 68-93.

[4] Nodelman, S. The Rothko Chapel paintings: Origins, structure, meaning. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997.

[5] Elkins, J. Pictures and tears; a history of people who have cried in front of paintings. New York: Routledge, 2001, p. 11.

Multitemporal Sensations

by Lara Fresko Madra

The Fall of 2011 feels a lifetime away. And it is exactly the lifetime of Protocinema, which opened its first exhibition in Istanbul on September 12 of that year. This opening date coincided with the anniversary of Turkey’s 1980 coup-d’etat and tangentially avoided the anniversary of 9/11. Incidentally Dan Graham’s works on display were concerned with public space and social interaction, things that had been deeply impacted by the two events thirty-one and ten years ago respectively. One part unwittingly and one part unavoidably, Protocinema began its journey between New York and Istanbul by scrambling the present with multiple pasts. This exhibition’s opening does not coincide with anything off the top of my head. It does, however, coincide with the twenty-third anniversary of the founding of the search engine, Google: a technological tool that has made history and knowledge so much more accessible, and yet has also overwhelmed us with it.

Retrospection is one of the more common modes of our perception. And it may have been apt for Protocinema’s tenth anniversary exhibition to look back and take stock of the past decade. Yet this past decade has seen us to think in much more diverse temporal modes. Each date nowadays seems to carry with it the burden of anniversaries. Google celebrates great thinkers and books and events on its landing page; social media and our phones remind us of memories closer to us. Birthdays and world altering achievements appear alongside attacks, bombs, coups, protests, imprisonments, crises, fires, floods, hurricanes, losses. Their relations in constant shuffle, we have come to recognize that these anniversaries are subtended by long, protracted processes; deep, interlacing currents and countercurrents. Among them, global warming, species’ extinction, colonialism, capitalism. How do we survive at a time when the past resonates so strongly? Can we listen to these pasts that resonate so much like the five horsemen of the apocalypse to find new ways of knowing and understanding? Can we still imagine a future despite or through the static?

This exhibition was initially titled Imperceptible and Inconceivable. That is, not only unavailable to sensory perception but also excluded from imagination. Yet as blindsided or overwhelmed as our senses seem to be by global crises like global warming and COVID-19, imagination is not only alive and well but also thriving in a moment of multi-temporal glitch. The expansion of our temporal modes of grasp has brought with it new perspectives on materiality and sensibility, a reevaluation of what we know and how we know it, and a renewed embrace of fiction as something that is not quite opposed to fact but necessary for its conjuring.

Once Upon a Time Inconceivable presents in the storied time of fairy tales to articulate the varied and ever entangled ways in which we have come to actively live and perceive in a multiplicity of past, present, and future tense. Indeed, this exhibition is not so much a retrospective as it is an introspection. It asks after where to go from here; how to face the complex resonances of the past without being drowned by it. It is an anniversary. But not of something that is said and done but of something that is diffusely extant, ever changing, and still hopeful. Protocinema has, for the past decade, been a beacon for experimentation with its itinerant set-up and its vision that tended to the past, present, and future.

--

Elizabeth Grosz suggests that time is neither fully present, nor pure abstraction. Looking at it directly is impossible. We are too close to it, too far from it. She writes: “We can think it only in passing moments, through ruptures, nicks, cuts, in instances of dislocation.” Can artistic practice cut through time and space to engender perception? By the same token, can we imagine thinking of passing moments not just in retrospect or through the immediately visible but in ways that redistribute the temporal and sensible axes of our perception? The artistic milieux’s interest in history has been critiqued and complemented by non-human-centric temporalities of hauntology, geological, and ecological time. Memory has been reconsidered as a practice in the present tense rather one solely regarding the past. The hegemonic acceleration of globalized time has been challenged by discourses and actions towards decolonization and degrowth, each relating to how time is imagined, grasped, used, and abused. Each temporality and the permutations thereof relate, in distinct ways, to the visual and the sensible spheres. How we imagine and engage time is changing. Will this shift in sensibility change the ways in which we act?

Banu Cennetoğlu’s citation of Octave Mannoni’s infamous “I know very well, but nevertheless”, spelled out in Turkish with letters made of Helium-filled balloon, in IKNOWVERYWELLBUTNEVERTHELESS (2015-21), embodies and performs the multiple temporalities along with conflicts of perception and in/activity. The statement points to a state of subliminal or willingly repressed state of awareness, implicating both the naïve sentimentalists and the witting realists in the face of surreal times. As the letters slowly deflate, move lower on the wall, and lose their shape, the first moments when they were blown up, the opening of the show will have faded from our field of recollection. One disaster strewn after another on a global field of vision does not yield a narrative history but rather, as Walter Benjamin would have it, a pile of debris. Neither the deformation of the letters nor the piling debris, however, mark a rupture between the past and the present. They mark rather, a complex, non-linear relation.

Istanbul is the epitome of this kind of multidimensional historical landscape where spolia –reused architectural parts from old, demolished (or destroyed) structures –are an inherent part of the architectural fabric and when you dig deeper, you might encounter archeological traces from all the way back to 6000 B.C. In such a landscape, what is buried haunts our imagination while much that is present and visible only surfaces in our consciousness occasionally. Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s practice has long considered the cartoonish trope of sweeping the dust of history under the rug. In her new commission for Protocinema, titled Skindeep (2021), she explores the way architectural façades and coverings such as marble and carpet plaster over scaffolding, disguising complex cultural and architectural provenance. Appearances relate somewhat contingently to what we might perceive. And time complicates this contingent relation even further.

As a deeper understanding of slow violence – that is the unspectacular yet profound ways long term, often latent effects of ecological and social violence are exerted, experienced, and perceived– is formulated and the once impending climate catastrophe has jumped from silver screen dystopias to the incessant hum of the news, the hopeful trust in the modernist ideology of progress has been waning. The hegemony of the visible in our historical imaginary is in crisis. The hold of official history is being challenged by falling monuments and viruses too small to be detected by microscope. Abbas Akhavan’s installation, spring (2021), made of frozen pipes salvaged from dismantled public fountains imagines the underbelly of public visibility by introducing freezer liquid into its systems. Meanwhile Gülşah Mursaloğlu’s Merging Fields, Splitting Ends (2021) sets up another system made up of kindred materials from under the surface of the earth: metal, potato, and water. These elements are activated by heat and time to create a twofold increase in entropy. The vapor from water heated inside enameled vessels are directed towards potato plastic –a new generation technology that relies on the perishability of the potato rather than its storied durability. Temperature, like time, not only creates an irreversible entropic reaction within the system but also overflows from the works into the Beykoz Kundura Factory space and seeks our attention as much through what is immediately visible within the space as through our sensibility to the micro-climate it creates.

Anniversaries are often blown out of proportion. 2021 will see many art institutions in Istanbul mark their 10th anniversaries alongside that of Protocinema. This cluster of anniversaries say as much about 2011 and the years leading up to it as they do about the years since. It is difficult to slice up time, assemble a summary of the most important moments, delimit the reach of influence between years and the events. If nothing else, this past decade was marked by a rediscovery that perhaps it was not the singular moments that mattered so much as the time and the ways it stretched out, slowed down, accelerated, ebbed, and flowed. Protocinema has been nimble within these turbulent waters; negotiating time and space with each exhibition, location, and collaboration, and its transforming and transformative vision. Once Upon a Time Inconceivable, as Protocinema’s previous endeavors, boasts a wide selection of sensory, aesthetic, and intellectual provocations that tend to our imagination.

Further reading:

Batuman, Elif. “The Big Dig,” The New Yorker. August 31, 2015.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Survival of the Fireflies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Grosz, E. A. The Nick of Time: Politics, Evolution, and the Untimely. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2004.

Gürbilek, Nurdan. The Orpheus Double Bind. Translated by Victoria Rowe, Holbrook. Hong Kong: Asia Art Archive, 2021.

Lambert, Leopold (eds.). “They Have Clocks, We Have Time” The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies Issue 36, Summer 2021.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Parikka, Jussi. A Slow, Contemporary Violence: Damaged Environments of Technological Culture. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016.

Rothberg, Michael. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Saybaşılı, Nermin. Mıknatıs-Ses: Rezonans ve Sanatın Politikası. Istanbul: Metis, 2020.

No small itch.

by Mari Spirito

Let’s imagine a future moment where we look back to today’s world: how would we narrate the human condition now? For example, Once Upon A Time there was a moment in history of unthinkable destruction, loss and grieving. The darkest depths of human corruption and violation were revealed alongside a stillness that embodied both terror and deep reflection.

Once Upon A Time, I made a phone call to one of my sisters who had recently moved to San Francisco from Boston. Her friend answered and told me that she had been abducted by the Unification Church, aka Moonies, a destructive mind control group. She has been lost to us in so many unimaginable ways since then. In the years that followed, I reluctantly learned about behavior modification, thought reform, cults and the realm of the "mind as the final battleground". In fact, mind control is surprisingly easy; it is a cocktail of depravations including: information, sleep, privacy, nutrition, mixed with forced confessions and old-school coercive conformity. Eating starch and sugar together, for example, makes an individual more compliant. I am mentioning this here because while perception and realization may be wide topics for an exhibition, that all art could potentially fit into, this personal experience underlining the power and fragility of our minds constitutes the fountainhead of this exhibition. As in our contemporary culture, in which totalitarian tactics have become the norm, the stakes are even higher on how perceptions are formed and what behavior/actions arrive as a result. Supporting freedom of mind and creating alternatives to undue influence are at the core of what we do.

Once Upon A Time, I had a longing for a plurality, to add on/converge with a multitude of voices, worldviews, with the tools that were available to me: art and conversation. I felt a barrier between me and my art experiences I had back then and imagined an immediate space for me to come to my own realizations. In hindsight, I see that I was taking back my art experience from the confines of capitalism and conformity, in my own way. I did this for me; anyone who wants to join is welcome anytime. This was no small itch. "Like a splinter in your mind driving you mad." At that time, the idea of remote-office, a decentralized art organization, decidedly free of brick and mortar, permaculture approach to spaces and resources, was inconceivable. For example, to use what is already there, "waste not, want not" content rich and lean materially. Only ten years ago, any micro-business needed a physical space to be legitimate and a website for reach. Today, you need a website to be legitimate and social media for reach, and there is a growing global proliferation of independent initiatives (art & otherwise) that operate this way. From this crush of insistent collapse a "take back the night" approach to all aspects of our lives has come up. Even dying and death are being wrestled from corporate systems of extraction and exploitation. To put "our money where our mouth is" we took our already decidedly modest way of working, doing the most we can with minimal resources, one step further.

We felt excited about doing what we can by adapting even more sustainable exhibition-making models that reduce exploitation (of natural resources, labor and knowledge) and consumption (almost no shipping, flying or material waste). For example, artist Abbas Akhavan has been working in Istanbul for many years and lives in Montreal. He was happy to take on the challenge to work with us to create a new artwork from afar that is made by our team, under his close instruction. Doing so, he is incorporating the current conditions and concerns into his material and process; it is another evolutionary step, collaborative instruction art. Abbas has worked with many different fabricators here, from bronze casting to tailors, and was also happy to reduce his flights in light of the eco-crisis. Collaborating with two innovative young architects, Eda Hisarlıoğlu and Awab Al Saati, we came up with the exhibition design, walls, signage and seating which will all be recycled. The walls in Once Upon a Time Inconceivable are made of cardboard boxes, which form towering grids and especially in this warehouse give the feeling of temporality. This whole show appears as if it could be packed in all these boxes and be gone the next day. Maybe it makes it slightly more exquisite because we know it is here just for now, just like life itself. Maybe this feeling that everything is fleeting is how we feel all the time. This process is unfolding before our eyes and requires time and space. One recurring question is "What happens when we value the process, the person and the artwork equally?" Running beside that is “Do we have the capacity to change our own thinking, actions, to break cycles of violence, once and for good?" The book on "how to" make and run your own art organization, working locally within a global network, is being written now, by all of us.

Once Upon A Time, there was a specific place. Protocinema is known for our site-aware commissions, responsive to locale.There is a logic behind what may seem like madness. Children need a solid home, community and unconditional love for their development and well-being. Inseparably, there is an equal need to go out into the world, learn and engage. To be both grounded and mobile are basic human rights and beautiful parts of life. I would even say that this is as essential as breathing itself, internal and external, to inhale and exhale, both are equally indispensable. The exact opposite of forced migration and travel bans, two sides of the same coin, as the adage goes. That said, not only have I been drawn to make Protocinema both based in Istanbul and New York, yet to also radiate out of these places programmatically. For example, our annual screening tour, this year’s titled Permanent Spring, Delayed Bloom, curated by Asli Seven, goes out to twelve cities. Similarly, we also made a group show, A Few In Many Places, (in 2020 and again in 2021, this time co-curated with Abhijan Toto) that took place across six cities. We are focused on our locale, site and place, as our solid home and exhale to spread out to additional places for our mobility and further engagement.

In Once Upon A Time Inconceivable, we have two artists who have made work in this mode: both grounded and radiating. Paul Pfeiffer’s Orpheus Descending (2001), is footage played in real-time the full life span of a flock of chickens, which, may feel excruciatingly slow, yet that is the way it is. We experience this video the same way that we experience our own lives. For example, we have to wait about ten (long) days for the baby chicks to even hatch out of their eggs. This also counters art as a narrative edutainment, instead of being a lived experience, his video is more along the lines of experimental film and life itself. This story is being told in our exhibition, yet it does not stop there. Paul asked us to site five additional screens, running the same real-time videos of his chickens (in memorial, they have been dead for twenty years) in sites around Istanbul: Moda, Beyoğlu, Kurtuluş, Beykoz town center, and so on. In this way, the lives of passerby run parallel to the lives of the chickens. This happens slowly over time in many places in the city at the same time. Another artwork in this show that also does this, radiating out, is Mario García Torres’ Spoiler Series (n.d.), which will take two forms. One is that of small silk-screened painted canvases hanging in this warehouse cum exhibition space. As the Spoiler Series are all spoilers of well-known films, the second form of this artwork is that of posters, installed in movie poster kiosks all over Istanbul. It is almost as if his canvases transformed themselves to be able to walk around the city on their own. This sowing of an artwork into a multitude of additional physical places, adapting to its context, mirrors how Protocinema activates as an organization and also expands the breadth of this specific show.

Once Upon A Time, I had another phone call, this time from one of my brothers, about our lost sister, a few years ago. I was looking into the garden of the French Palace in the company of debating seagulls. I cannot recall exactly what he said yet I can feel that sensation in my body as I write this today. That moment was when I had the realization that my sister may never be well in this lifetime. For thirty years, I had done everything I could for her. I always thought that one day she would lift her head and everything would be different. I may have known intellectually that she had crossed the line of no return, yet I had not really realized what was right in front of me. What is the space between realization and acceptance of what is known? Of course, the past eighteen months have given all of us much suffering, taken many precious lives and have also allowed the time to each have our own game-changing realizations. Re-thinking and realizations are such prevalent outcomes of lockdown that mainstream media was full of articles on this phenomena. The Economist published "My covid epiphany: a year of doing nothing changed everything" on May 12 and the New York Times had many stories, such as "Welcome to the YOLO Economy", You Only Live Once, which lead so many people to quit their jobs to go party that it made a significant fiscal impact and companies are hard pressed to find people willing to work, in April 21, this year.

What can one little itinerant art organization do? What can each of us do? What can be done when we do it together? In Olivia Laing’s words:

There are so many things that perhaps art can’t do. It can’t bring the dead back to life; it can’t mend arguments between friends, or cure AIDS or halt the pace of climate change. All the same, it does have some extraordinary functions, some odd negotiating ability between people, including people who never met and yet who infiltrate and enrich each other’s lives. It does have the capacity to create intimacy; it does have a way of healing wounds, and better yet of making it apparent that not all wounds need healing and not all scars are ugly.

How do realizations, these eureka moments, take us to places we never imagined, to do things we never knew existed, in ways beyond conception? This is one milestone among many, I do not know what will happen down the road, I just know that we will go there together; it will be something we cannot see from here, something completely inconceivable.